6 Distractions To A Drivers Concentration

Driver distraction research has a long history, spanning nearly 50 years, but intensifying over the last decade. The dominant paradigm guiding this research defines distraction in terms of excessive workload and limited attentional resources.

This approach largely ignores how drivers come to engage in these tasks and under what conditions they engage and disengage from driving—the dynamics of distraction. The dynamics of distraction identifies breakdowns of interruption management as an important contributor to distraction, leading to describe distraction in terms of failures of task timing, switching, and prioritization.

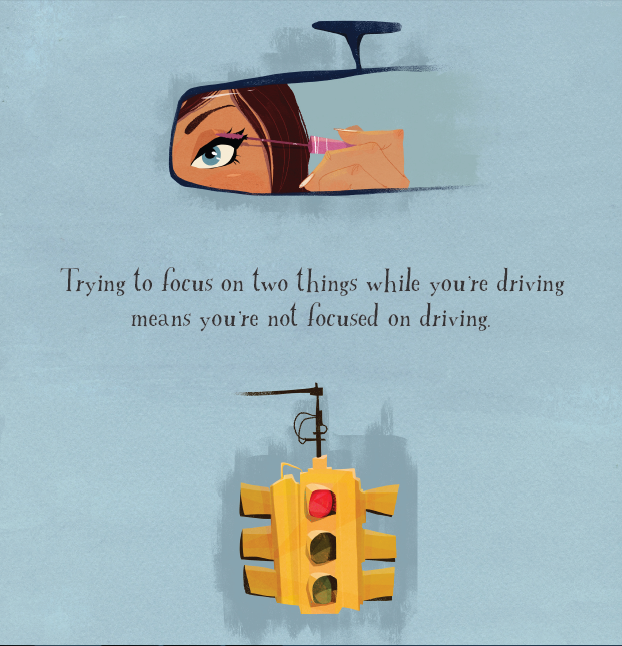

On average, a driver engaged in a distracting activity once every six minutes. People or events (22 incidents), lack of concentration (11), and passengers (6). Distraction can occur any time a driver’s hands, eyes, or concentration are diverted from driving safely. Cellphones may increase the risk of distraction, but non-driving activities—such as eating, drinking, applying makeup, rubbernecking at accident scenes, speaking with passengers etc. All increase the risk of an accident.

The dynamics of distraction also identifies disengagement in driving (e.g., mind wandering) as a substantial challenge that secondary tasks might exacerbate or mitigate. Increasing vehicle automation accentuates the need to consider these dynamics of distraction. Automation offers drivers more opportunity to engage in distractions and disengage from driving, and can surprise drivers by unexpectedly requiring drivers to quickly re-engage in driving—placing greater importance of interruption management expertise. This review describes distraction in terms of breakdowns in interruption management and problems of engagement, and summarizes how contingency, conditioning, and consequence traps lead to problems of engaging and disengaging in driving and distractions. INTRODUCTION Society has been driving with distraction since the first automobile. Even the specific focus on phone conversations as a source of distraction has a history stretching back almost 50 years ().

The dynamics of distraction also identifies disengagement in driving (e.g., mind wandering) as a substantial challenge that secondary tasks might exacerbate or mitigate. Increasing vehicle automation accentuates the need to consider these dynamics of distraction. Automation offers drivers more opportunity to engage in distractions and disengage from driving, and can surprise drivers by unexpectedly requiring drivers to quickly re-engage in driving—placing greater importance of interruption management expertise. This review describes distraction in terms of breakdowns in interruption management and problems of engagement, and summarizes how contingency, conditioning, and consequence traps lead to problems of engaging and disengaging in driving and distractions. INTRODUCTION Society has been driving with distraction since the first automobile. Even the specific focus on phone conversations as a source of distraction has a history stretching back almost 50 years ().

Given that distraction and inattention account for an estimated 25% of motor vehicle crashes, distraction remains an important concern and an area of active research (;; ). Rapid changes in information technology suggest that distraction may be an increasingly urgent problem. Smart phones, wearable devices, and internet-enabled vehicle systems all connect drivers to social networks and a rapidly increasing volume of information that has the potential to distract. Increasing vehicle automation may compound these trends by removing many driving demands, which may tempt drivers to engage in distracting activities (). Drivers who succumb to these temptations might be particularly vulnerable to situations that the automation cannot accommodate. More distractions and more opportunities to engage in those distractions combine to make driver distraction a particularly prominent research, design and policy issue ().

Distraction is often framed in terms of mental workload and so this paper begins with a brief discussion of distraction as instances of excessive mental workload, which provides a context for an alternate perspective that considers distraction as a breakdown in the dynamic process of attending. Two important types of breakdowns include poorly timed interruptions to driving and general disengagement from driving. Vehicle automation may exacerbate those of these breakdowns. The paper concludes by describing mechanisms guiding engagement and disengagement in driving and non-driving tasks.

ATTENTION AND ATTENDING Addressing driver distraction demands a clear definition and theoretical orientation. Many definitions of driver distraction have been developed and the following reflects an integration of many of these: “Driver distraction is a diversion of attention away from activities critical for safe driving towards a competing activity.” (, p. As with most definitions of distraction, attention and the process of dividing attention between the road and some competing activity play a central role.

Perhaps most critically, attention concerns whether a driver’s eyes are directed toward the road—long glances away from the road are particularly risky (). This definition is also consistent with distraction as the division of limited attentional resources, which has provided a theoretical basis for mental workload (; ). This definition also implies that distraction reflects a process of shifting and engaging attention over time (; ).